- Home

- James Oakes

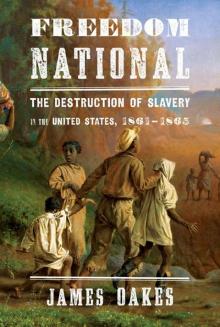

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 Page 6

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865 Read online

Page 6

The previous generation of mainstream politicians, willing to wait passively until slavery gradually disappeared and deferring to the protection the Constitution afforded slavery, had opposed the very idea of a national antislavery politics. But by the 1850s Seward and like-minded politicians were arguing that although the federal government could not directly abolish slavery in the states where it existed, the Constitution nevertheless severely circumscribed the reach of slavery, restricted it to the states where it existed, and empowered the federal government to act aggressively against slavery everywhere else. “Immediate” abolitionism had opened a space for a truly national antislavery politics by developing a specific set of federal policies—policies that would be implemented immediately though designed to bring about the ultimate extinction of slavery. Charles Sumner spelled out those policies in his first major antislavery speech as a member of the U.S. Senate, “Freedom National; Slavery Sectional,” delivered on August 26, 1852:

In all national territories Slavery will be impossible. On the high seas, under the national flag, Slavery will be impossible. In the District of Columbia Slavery will instantly cease. . . . Congress can give no sanction to Slavery in the admission of new Slave States. Nowhere under the Constitution, can the Nation, by legislation or otherwise, support Slavery, hunt slaves, or hold property in man.47

This was a prescription for building a “cordon of freedom” around the states where slavery already existed. Confined within those limits, slavery would eventually shrivel and die. The policies would be implemented immediately, but abolition itself would be gradual as the slave states succumbed to the pressure from the federal government. Wherever the federal government was sovereign—on the high seas, in the western territories, and in the nation’s capital—slavery would be abolished by the national government. Federal officials would not be compelled to hunt down and re-enslave a species of “property” that existed only under the law of the southern states. Sumner and his fellow radicals wanted to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850; antislavery moderates wanted it revised to restore the right of states to protect their own citizens. But by 1860 most Republicans agreed that enforcement of the fugitive slave clause of the Constitution should be returned to the states.48 They also agreed with Sumner that no new slave states should be admitted to the Union. That way the Slave Power’s influence on federal policy would be steadily diminished and ultimately destroyed.

Such was the first scenario for abolition to emerge from antislavery politics. It was based on several crucial premises: that slavery had no legal existence outside the states that sanctioned it; that because the Constitution recognized slaves only as persons, there was no such thing as a constitutional right of property in slaves; that the federal government was therefore free—maybe even obliged—to attack slavery wherever the Constitution was sovereign; and that slavery was so weak that it would ultimately succumb to the pressure of federal antislavery policies. What had already happened in the North would eventually happen in the South: the slave states themselves would realize that slavery was holding them back economically, disrupting the social order, and promoting political instability. With a strong nudge from the federal government, the states would then abolish slavery on their own.

The opponents of slavery also had a second scenario for a federal attack on slavery, one that rested on many of the same premises but that would also, under certain circumstances, empower the federal government to enter the southern states and actually emancipate slaves.

EMANCIPATION AS A MILITARY NECESSITY

In 1839, shortly after the slave ship La Amistad sailed from Havana on its way to the Cuban town of Puerto Principe, some of the fifty-three slaves on board rose in rebellion, murdering the captain and his cook. Two crewmen escaped in a boat and made their way back to Havana, but the two Spanish traders who had purchased the slaves, Pedro Montez and José Ruiz, could not get away. The leader of the rebels, whom his captors named Joseph Cinqué, ordered the two traders to sail the Amistad back to his home among the Mende people of West Africa, in Sierra Leone. Not knowing how to sail a ship, Cinqué and the rebels were forced to rely on the two Spaniards who had purchased them. During the day Montez and Ruiz complied, but by night they shifted course and sailed the boat in a northwesterly direction. The Amistad ended up not on the West African coast but on the north shore of Long Island, in New York. There Cinqué and the rebels were arrested and taken to Connecticut for trial.49

Abolitionists immediately recognized the significance of the case and arranged for attorneys to represent the rebellious slaves. They were acquitted twice, in both district and circuit courts, but the administration of President Martin Van Buren, anxious to establish its bona fides with proslavery southerners, repeatedly appealed the decisions, hoping for a conviction that would allow the government to send the captive Africans to slavery in Cuba. Prejudging the outcome, the secretary of state gave assurances to both Cuban and Spanish officials that the slave traders—Montez and Ruiz—would be vindicated and their slave “property” returned to them. Once again the federal government was siding with slave owners in a case of slave rebellion on the high seas. Officials appealed every decision to free the slaves, and in 1841 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, where the rebels were defended by John Quincy Adams.

Adams’s extended oral argument—it took two full days to deliver—was a précis of antislavery constitutionalism. Pointing dramatically to a copy of the Declaration of Independence hanging in the courtroom, Adams told the justices that he knew of “no law” that “reaches my clients . . . but the law of nature and of Nature’s God.” On the high seas there was no “municipal” or “positive” law of slavery, only the law of nations. Hence the Africans were wrongly arrested “as property, and salvage claimed upon them.” The secretary of state had gone so far as to declare that the Africans were “Spanish property.” But Adams dismissed the idea, declaring that the Constitution consistently “represented” slaves as persons and never as property. As persons under the Constitution and as human beings under the laws of nature, Adams argued, the Amistad slaves had reclaimed their inherent right to freedom by rebelling against their captors. Invoking the term that was becoming popular among abolitionists, Adams declared that the Africans aboard the Amistad were “self-emancipated.” He denounced the Van Buren administration for sympathizing with the two Spanish “slave dealers” and for assuming that “all the right” was “on their side and all the wrong on the side of their surviving self-emancipated victims.” By their rebellion aboard the Amistad. Adams declared, the Africans had “restored themselves to freedom.”50

This was not entirely new reasoning for Adams. Under the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution, and a decade later under the terms of the Jay Treaty, the United States was forced to accept—over the vehement objections of southern slaveholders—that the British would not compensate Americans for slaves liberated in wartime. Later, as secretary of state, Adams himself had demanded reparations for the slaves liberated by the British during the War of 1812. But by 1820, when a dispute over the requirements of the Treaty of Ghent could be settled only by arbitration, Adams conceded that the British did not owe compensation for slaves they emancipated during the war. The dispute centered on when the war actually ended; the British would owe compensation only for slaves freed after that date. By the time he returned to Congress in the 1830s, Adams not only was aware of the historical precedents for wartime emancipation, but also invoked those precedents as a threat. His warning was prompted by the “gag rule” that Congress imposed on itself to prevent the reception of antislavery petitions. Adams led the opposition to the rule. Initially his defense of the petitioners reflected his deeply conservative impulses: superiors had an obligation to acknowledge the petitions sent up by their inferiors. That would change. Adams’s courageous stance attracted the attention and ultimately the friendship of leading abolitionists and antislavery radicals, among them Weld and Giddings. The gag-rule debates

dragged on for years, and by the early 1840s Adams was so closely aligned with the antislavery movement that abolitionists solicited him to argue the Amistad case before the Supreme Court, and by then Adams was willing to do so. His impeccable conservative credentials no doubt made Adams’s support for antislavery petitioners all the more impressive, but by the 1840s abolitionists were attracted to him primarily for his defense of military emancipation.51

During the congressional debates over the gag rule, Adams argued that under certain circumstances the federal government had the power to emancipate slaves in the southern states. Emancipation of the enemy’s slaves in time of war was widely accepted under the law of nations, Adams argued, and it was just as widely understood that the Constitution incorporated the law of nations within itself as part of the war powers. “This power is tremendous,” Adams declared, and “it is strictly constitutional.” Suppose Congress was called on to raise an army and allocate the funds necessary “to suppress a servile insurrection,” he speculated, “would they have no authority to interfere with the institution of slavery?” Suppose as well that the terms of the peace treaty ending a civil war required “the master of a slave to recognize his emancipation.” In such a case, Adams asked, would Congress “have no authority to interfere with the institution of slavery, in any way?” Adams did not deny that in ordinary times, in times of peace, Congress had no authority to interfere with slavery in the state where it already existed. But in times of war the laws of war applied, and under the laws of war Congress would have the power to “interfere” with slavery by emancipating slaves. This was emancipation as a military necessity.52

No one doubted that the Founders had incorporated the law of nations—which included the laws of war—into the Constitution they drafted in Philadelphia. There was not much agreement, though, about what the “laws of war” actually allowed the government to do. The standard treatises of Grotius, Pufendorf, and Vattel said nothing about slavery and emancipation. Their American interpreters—Henry Wheaton and Henry Halleck, for example—were likewise silent on the matter. Those claiming that the government could emancipate slaves as a military necessity in time of war were unable to cite a reputable authority on the law of nations. Nevertheless, prominent legal theorists, notably Joseph Story, generally agreed that the laws of war invested governments with extraordinary powers, and that the extent of those powers was to be found not in statutes or constitutions but in customary practices. What supporters of military emancipation could not find in theory they found instead in history.

Precedent after precedent demonstrated that emancipating an enemy’s slaves was widely accepted as a legitimate weapon for suppressing rebellions, prosecuting wars, and securing military victory. The British had done it to the Americans, twice, first during the War of Independence and then in the War of 1812. On both occasions the British offered freedom to American slaves; on both occasions thousands of slaves ran for freedom to British lines; on both occasions the Americans—not least of them John Quincy Adams—demanded that the slaves be returned when the fighting stopped; and on both occasions the British refused to re-enslave those they had emancipated. A generation later Adams was citing historical examples as evidence that wartime emancipation was customary practice and as such valid under international law. Some of his most telling examples were homegrown. Even as southern congressmen were denouncing the very idea of military emancipation, U.S. generals in Florida were offering freedom to runaway slaves who abandoned their Seminole protectors and returned to American lines. When the Second Seminole War officially ended in August of 1842, the U.S. government honored the military emancipations, freeing hundreds of slaves and refusing to compensate their outraged owners. Adams likewise cited the recent wars of independence in Latin America. In 1814 General Pablo Morillo offered freedom to slaves who enlisted in the royal army and helped suppress the independence movement. A year later Simón Bolívar responded with an emancipation edict of his own, offering freedom to slaves and their families who joined in the rebellion against Spanish rule. There was nothing new in any of this. Arming slaves and emancipating them for their service was a venerable tradition, as familiar to the Greek and Roman empires of antiquity as it was to the Spanish, French, and British empires of the early modern Atlantic. Throughout human history, warfare has been one of the most common sources of manumission.53

What made John Quincy Adams’s recitation of the precedents so shocking was the constitutional argument he used to justify them. Amid the ongoing debates over the gag rule, for example, even Joshua Giddings included among his resolutions one that recognized that the states had the “exclusive right of consultation on the subject of slavery.” It was a measure of how thoroughly radicalized Adams had become that he declared his opposition to Giddings’s otherwise standard disclaimer: the federal government would refrain from interfering with slavery in the states only so long as the states themselves were “able to sustain their institutions.” But if a rebellion were to break out in the slave states, Adams warned, “and two hostile armies are set in martial array, the commanders of both armies have power to emancipate all the slaves in the invaded territory.54

Adams’s influence on the antislavery movement can scarcely be exaggerated. After 1836, when he first broached the argument, variations on the theme of military emancipation quickly made their way into abolitionist writings and eventually into antislavery politics. In 1838 Weld—who would later work closely with Adams in Washington—argued that Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, which authorized Congress to suppress domestic insurrections, could be used “as well to protect blacks against whites, as whites against blacks.” In providing “for the common defence,” Weld added, Congress “would have the power to destroy slaves as property . . . while it legalized their existence as persons” by arming them, out of “necessity,” in the national interest. The Liberty Party platform echoed Weld’s argument when it declared that in authorizing Congress “to suppress insurrection,” the Constitution “does not make it the duty of the Government to maintain slavery.” On the contrary, “[w]hen freemen unsheath the sword,” the platform announced, “it should strike for Liberty, not for Despotism.” By 1850 even William Seward broached the possibility of military emancipation in his “higher law” speech. He fully expected slavery to die gradually, but if the slave states rebelled against the Union by seceding, it would lead to “scenes of perpetual border warfare, aggravated by interminable horrors of servile insurrection.” The prospect of peaceful, gradual, compensated emancipation would vanish. Instead civil wars would ensue, “bringing on violent but complete and immediate emancipation.” Freedom “follows the sword,” Seward declared, and in the great confrontation between liberty and slavery there can be only one outcome: slavery must yield “to the progress of emancipation.”55

Seward’s words once again mark the migration into the political mainstream of the second abolitionist scenario for a federal attack on slavery—military emancipation as a means of suppressing domestic insurrection. Its advocates did not repudiate the federal consensus. They still acknowledged that the U.S. government had no power to interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed, at least not in peacetime. But in wartime, if the Union was called on to defend itself against domestic insurrection, the rules that normally restrained Congress gave way to the “necessity” of national self-preservation. Slavery’s opponents argued that military emancipation was fully constitutional because it was the accepted practice under the laws of war, laws which were themselves embedded within the Constitution.

Unlike the proposal to promote state abolition through federal containment—which was developed by antislavery radicals beginning in the late 1830s—military emancipation had its origins in the respectable northern elite. To many an American eye, John Quincy Adams was the very essence of New England conservatism. In developing his own thoughts about slavery and the war powers, Adams himself was influenced by Joseph Story, another bastion of the northeastern

legal establishment. As a sitting justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, as a professor at the Harvard Law School, and as a prolific legal theorist, Story did as much as anyone to develop and broadcast the proposition that the law of nations not only was an integral part of the Constitution but also invested the federal government with extraordinary powers to suppress insurrection and restore domestic tranquility. Yet despite its respectable pedigree, radicals were quick to appropriate the concept of military emancipation, and in the end the lines of influence between abolitionism and conservatism ran in both directions.

Sensing a potential convert, Giddings and Weld huddled together with Adams at a boardinghouse in Washington, nudging him toward the abolitionist constitutionalism that was so strikingly apparent in the Amistad brief. Story had incorporated an expansive version of the Somerset principle in an influential treatise on the conflict of laws. “Suppose a person to be a slave in his own country,” Story asked, “is he upon his removal to a foreign country, where slavery is not tolerated, to be still deemed a slave?” Certainly not in England, Story answered. “[A]s soon as a slave lands in England, he becomes ipso facto a freeman.” More important, the same rule applies under the U.S. Constitution. “[F]oreign slaves would no longer be deemed such after their removal thither.” By this reasoning the Amistad captives were free as soon as they set foot on American soil, precisely as Adams claimed. Story himself had been too busy with his work on the Supreme Court to proofread the galleys for his treatise, so he assigned the task to his brilliant young protégé at the Harvard Law School, Charles Sumner. And it was Sumner who, upon hearing of the attack on Fort Sumter, marched from the Senate to the Executive Mansion waving copies of Adams’s speeches in President Lincoln’s face. Throughout the Civil War, in all of the numerous congressional debates over the constitutionality of military emancipation, one Republican speech after another invoked the authority of the canonical theorists of the law of nations. But more than Grotius and Vattel, John Quincy Adams was the name that came most often to Republican lips. He taught them that even though the federal government could not abolish slavery in a state, it could emancipate the slaves in any state that was in rebellion against the United States.56

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865

Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861-1865